New possibilities for breakthrough performance provided by the emergence of new enabling technologies and digitalisation seem to be endless. Explosive advances in IT have enabled the dissemination, analysis, and use of data and information from and to customers and suppliers and within enterprises, in new ways and in time frames that impact processes, organization designs and strategic competencies. Computer networks, open systems, client-server architecture, groupware, electronic data interchange and analytics have opened up the possibilities for the integrated automation of business processes. Neural networks, enterprise analyser approaches, computer-assisted software engineering, and mobile object-oriented programming now facilitate systems design around many processes in most organisations.

The pace of change has, of course, been enormous and IT systems unavailable just a few years ago have enabled sweeping changes in business process improvement, particularly in business systems. Just as statistical process control (SPC) enabled manufacturing processes to be improved by controlling variation and improving efficiency, so technology is enabling all types of processes to be fundamentally restructured.

Technology and data in itself does not offer all the answers of course. Some companies putting in major new digitalisation, machine learning and artificial intelligence systems have achieved only the automation of existing processes. Moreover, quite often different functions within the same organization have systems that are incompatible with each other. Locked into traditional functional structures, some managers have spent large amounts on technology and digitalisation that have not been integrated cross-functionally. Yet it is in this cross-functional area that the big improvement gains through IT are to be made. Once a process view is taken to designing and installing any technology, it becomes possible to automate cross-functional, cross-divisional, even cross-company processes.

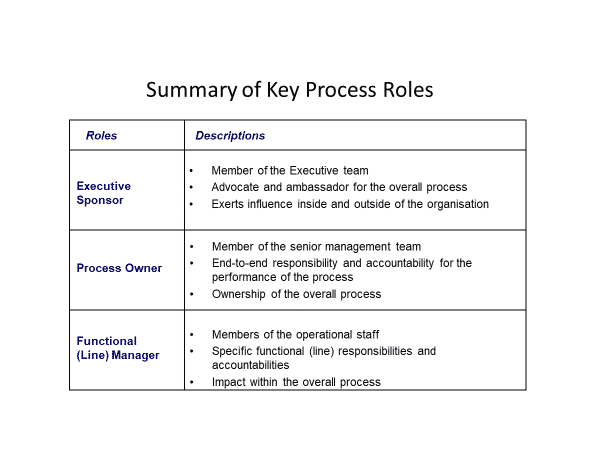

Perhaps the most visible difference between a process management enterprise and a more functionally based one is the existence of process owners – management layers with end-to-end responsibilities for individual processes (see Table – Summary of key roles). They have real responsibility for and authority over the process design, operation and measurement of performance. This can require changing from being functionally driven, which can mean a major cultural challenge for the organisation. Process owners cannot simply adopt a command and control style, so their ability to influence is at least as important to effective process management as structure.

Many organisations have realised that to be cost-effective, competitive and indeed world-class, they must ensure that all processes are understood, measured and in control. Almost everyone needs to be educated in process management and improvement and shown how they are part of a supplier-inputs-process-outputs-customer chain (SIPOC). This reinforces that these chains are interdependent and that the all processes support the delivery of products or services to customers.

Operators of every process need to be properly trained, have necessary ‘instructions’ available, and have the appropriate tools, facilities and resources to perform the process to its optimum capability. This applies to all processes throughout the organisation, whatever the outputs, including those in Finance, Human Resources and generally shared services areas.

In many process managed organisations this type of approach has changed the way employees are developed, emphasising the whole process rather than narrowly focussed tasks. It often requires fundamental changes to cultures, stressing customers and process based teamwork, rather than functionally driven objectives. Creativity and innovation in process improvement should be recognised as core competencies, and the annual performance reviews and personal development plans should be linked to these.

The first thing that top management must recognise is that moving to process management requires much more than re-drawing the organisational chart or structure. The changes needed are often fundamental, leading to new ways of working and managing, and these will challenge any company or public service organisation.

Most organisations are currently facing a large number of changes and initiatives, often driven by technology advances, customer or government demands, available software, and so on. Before implementing process management, therefore, a senior management team needs to examine closely all its current change initiatives, using simple frameworks, to prune those that are not relevant to a process managed business and combining/rationalising those that are.

The introduction of process management can be driven or directly connected to a strategic initiative, such as reducing non-value added time through ‘Lean’ approaches, increasing customer satisfaction, reducing working capital (perhaps tied up in work-in-progress), an enterprise resource planning (ERP) implementation, changes in technology, or introduction/expansion of digital-business. The application of new enabling technologies is an ideal time to review the design and configuration of key processes. Failure to do so could lead to missed opportunities to extract maximum benefit from the technology.

Implementing process management, like many change initiatives, cannot be a quick fix and it will not happen overnight. Top management need the resolution and commitment for major changes in the way things are structured, carried out and measured. As with all such implementation, it needs careful planning and an understanding of what needs to be done first. Things high on the list will be the establishment of a core process framework, aligned to the needs of the business, and the appointment of key process owners. A process based performance measurement framework, with appropriate data analytics, then needs to be set up to track progress. Delivering some tangible measurable benefits early on will help overcome the inevitable resistance. In one pharmaceutical company, for example, the success of the work on the product development and product promotion processes helped significantly the cause of process management and the company extended its approach into the supply-chain management and other processes.

As companies and public service organisations move inexorably towards the wider introduction of digitalisation to do business, this places a premium on rapid and fault-free execution of business processes. Putting a website or ‘app’ in front of an inefficient, ineffectual or even broken process will soon bring it to its knees, together with everyone working in it and around it. This will also bring “back-office” mistakes to the attention of the marketplace. Some of these processes will, of course, need to be re-designed – from customer order fulfilment to procurement. They will need to change “shape” as demands, technology and markets change. Without good process management in place this is going to be very difficult for functionally driven organisations.

Professor John Oakland